By Allen Fox, Ph.D. c 2018, all rights reserved

The lessons to be learned from the career of Roy Emerson are that the ability to work harder and longer than anybody else can make up for less than superb physical talent, and an optimistic, happy attitude can turn that work into a pleasure and a champion.

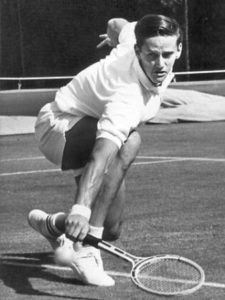

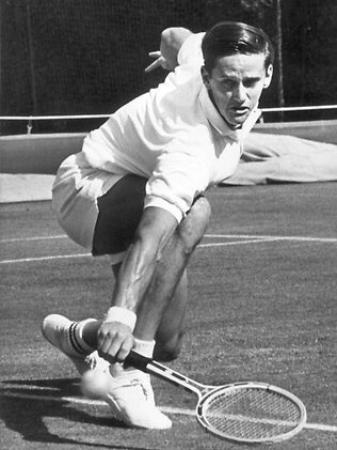

Roy Emerson (“Emmo”) held, until Pete Sampras came along, the record for winning more major championships than any other male tennis player (12). In his long and illustrious career he won Wimbledon twice, the U.S. Championship twice, the French Championship twice, and the Australian Championship six times. He dominated the world tennis circuit between 1963 and 1968, yet he was not a physical genius in the mold of Rod Laver, Pancho Gonzales, John McEnroe, Roger Federer, or Rafael Nadal. Emerson’s athletic ability was good but not great. He was well built, agile, and energetic, but lacked the gifted hands, blurring speed, and almost bionic physical abilities of many of the other famed champions. But if nothing else, Emerson was industrious. He loved the game and had a wonderful attitude that translated into a work ethic that was unmatched, even in those days when great work ethics were more commonplace.

In 1966 I was on an American team, along with Arthur Ashe, Charlie Pasarell, Dennis Ralston, and Cliff Richie, that traveled to Australia to play the major Australian grass court tournaments. During our trip we were fortunate enough to spend a week working out with the Australian Davis Cup team, which was preparing for the Challenge Round tie against Brazil. It was a great chance to get in shape.

Emerson showed us how it was done. He got up early and went for a long, hard run. Next came breakfast, followed by 2 ½ hours of the toughest on-court drilling imaginable. These drills consisted of constantly smacking balls as hard as you could and running all over the court. Emerson’s favorite was the “two on one” drill where two players on the baseline worked over one player at the net, moving him relentlessly from side to side and up and back until his legs wobbled, and he was sucking for air like a fish on the dock. When Emmo was one of the two baseline players, he kept up an incessant but good-natured verbal badgering of the player running at the net to squeeze the last drop of effort out of him. When it was Emmo’s turn he seemed able to go on running forever without needing emotional support from the players on the baseline. He liked it. On the other hand, by noon the rest of us were ready to drop.

After lunch we took a rest and then were back on the courts by 3:00 PM for three out of five set singles matches. These generally lasted for three or more hours in the burning Australian sun and left us dragging ourselves to the showers with visions of cold beers dancing in our heads. All except for Emerson, that is, because he went out to the grass field behind the courts to do an additional 20 minutes of sprints. As much as we all wanted to get into the best shape possible, no one else had the stomach for the sprints at the end of such a day.

Soon, though, Emmo was in to join us for beers in the bar. And his wonderful good nature was a joy to be around. He was always happy and everyone loved him. Win or lose, sick or well, injured or healthy, his spirits were always high. Years later at a small tournament, Charlie Pasarell and I went out to dinner with Emmo. His career had peaked years earlier and he was now being beaten regularly by younger players. Of course I remembered the old Emmo, and I asked if it was difficult for him, having been in the limelight as world champion for so many years, to lose to these guys or to sit on the sidelines in relative obscurity while the new generation got the trophies and television time? (Having once been on top and famous it is difficult for most players to give that up and fall back into the pack. At the peak of his career, Emerson was so well-known in Australia that a letter addressed simply to “Emmo, Australia” got to him.) Emmo’s answer showed the inner beauty of the man. He said, “When I was a young boy, raised on a farm in Queensland and milking cows, I was quite happy. Later, when I was number one in the world and winning the big tournaments, I was also quite happy. And I am quite happy now. I have enjoyed it all, and I’m still enjoying it.”

As was common in the 1960’s, Emerson’s style of play was aggressive, and he came to the net behind both first and second serves. This was an effective strategy in those days when the balls were lighter and faster, and most major tournaments were played on bad grass, where it paid to hit as many balls in the air as possible. He was a good, solid volleyer and had a particularly nasty backhand volley. On high balls he was able to slap flat winners off of this side with fearsome force. His conditioning and athleticism allowed him to dive and reach all but the most severe passing shots, so once established at net, Emerson posed a serious threat. On the other hand he did not have the deft touch of McEnroe or Gonzales so he had to rely more on power than guile.

His serve was good but not great. He had a funky motion with an extra jiggle or two before the actual swing began, but once started the action was smooth and rather conventional. Emerson’s groundstrokes were hit hard and flat or with slight topspin off of both sides. He won his matches by running industriously all afternoon and hammering away at every ball, regardless of the score or length of match. And he never tired. Emerson was as fresh and bouncy in the fifth set as he was in the first. And this was useful in those days before tiebreakers when sets could be decided at 12 – 10 or even 22 – 20, and matches could last, as they do now, over five hours. It demoralized opponents, facing a fifth set and feeling leg-weary after three or four hours on court, to look across the net and see Emerson bouncing around fresh and happy.

I played Emerson twice during my career. Obviously I was a class or two below him, but I did play him. The first time was in 1965 in the semi-finals of the Swedish National Championship at Bastaad, two weeks after he had won his second Wimbledon title. Having watched Emmo win multiple major championships over the years (he was not quite a legend yet, but close) I was intimidated as I walked on court, so intimidated, in fact, that I found myself playing to avoid embarrassment and to get a presentable score rather than to win the match. This is always a horrible approach. Not only do you forgo any chance of winning the match, but also, because you are so self-conscious, you even have difficulty getting the presentable score. I managed to get a presentable score (just barely) but derived no strong impression of Emerson’s strengths and weaknesses because I was so psyched out. He seemed to do everything quite well but nothing was overpowering or terribly impressive.

The next time we met was the following year (1966) in the finals of the Pacific Southwest Championship in Los Angeles on cement in front of a partisan home crowd, and I was playing out of my mind, fortunately. It was hard for me to judge Emerson’s game this time because I was in some sort of surreal zone. I had had a magic week and had reached the finals by beating the holders of three of that year’s major championships, (Manuel Santana, Wimbledon Champion; Tony Roche, French Champion; and Fred Stolle, U.S. Champion) on successive days and by the finals I literally could not miss. I was so confident and ahead of the ball that everything Emerson hit seemed to be in slow motion. I had remembered his serve as being pretty good, but on this day it seemed to just sit there and allow me to do pretty much what I wanted. I won the match relatively easily, but I could not get a proper feel for Emerson’s strengths and weaknesses because I never played a better match in my life!

Although Emerson’s record was wonderful and he dominated the major championships during the middle 1960’s one might wonder how he would have fared against the other great champions. This kind of question is always a matter of opinion rather than fact, but I would rate him as better than Arthur Ashe, Fred Stolle, Manuel Santana, John Newcombe, Tony Roche, Stan Smith, and Ilie Nastase because he beat these guys more often than they beat him, and he had a far better record in major championships. Finally, there is little question in my mind that Emerson was not as good as Rod Laver, Ken Rosewall, Pancho Gonzales, Bjorn Borg, Jimmy Connors, John McEnroe or Pete Sampras. They were magic people and were simply able to do more with the tennis ball than he was. But Emmo could certainly have beaten any of them on occasion (as he did beat Laver in the finals of the Australian and U.S. Championships in 1961), and, great competitor that he was, Emmo was no more than a whisker behind them.

Of course Emerson is not the only player to reach high goals via hard work and an excellent attitude as opposed to having raw physical talent. And though few will ever match his fantastic tournament record, anyone can improve by emulating, to whatever extent possible, his extraordinary work ethic and optimistic, positive attitude.

Leave a Reply